and, it continues... I had driven Manu’iki’iki up onto the raft of dead marsh grass to prevent being swept out into the Atlantic's chaotic breakers and breaking up on the sandbars at the mouth of Little Tybee Creek.

Standing there, the wind howling through the rigging and the spartina grass, it was time to put on the dry suit.

Eating slices from a salami, alternating bites with a hunk of gouda, I pondered the many different ways my next move could go wrong. Capsize, swept into the breakers and broken, swept into the breakers and broached, the wreckage piling up on Wassau Island’s southern shore…

I gave Fleetwood a status update and explained my current predicament. His recommendation was to wait for low tide, which jibed with what I thought best, so I got comfortable.

This wasn’t the first time I’d waited for water to come in or go out while in the marsh.

I sat on the rear deck of Manu’iki’iki, moving him out of the exposed mudbank as the water slowly dropped from the rapidly outgoing current.

At this point, I still generally trusted the tide predictions.

Gradually, a sizable sandbar at the mouth of the creek (noted only as a “changeable area” on my charts) was revealed by the dropping water level. I backed Manu’iki’iki out of the marsh where we’d waited and moved to the roomier real estate of the sandbar, scoping out Little Tybee Creek - or as much of it as I could see.

When I was convinced the current’s velocity had dropped and the ebb tide at last arrived, I braved the crossing with only the confoundingly relentless winds to contend.

It was an almost placid crossing, marred only by my lingering misgivings.

Beach Hammock is an elderly dune covered in palm trees, palmettos, live oaks, dune briars, cactus, yukka, and is surrounded by three distinct types of marsh habitat, all of which marked the land’s rising elevation where I landed.

Little Tybee Creek runs parallel to Beach Hammock and a line of dunes forms the south bank of the creek and bounds the marshes on that side of the hammock.

I opted to pitch camp on the dunes to avoid hauling gear through the marsh to the dense woods of the island proper; it also allowed me to tend to Manu’iki’iki as the tidewater began to flow.

I removed my bright orange PFD and drysuit and carefully put them away and thought confidently to myself, “I’m not getting wet today!”

I know that an exceptional spring tide could cover the area where I chose to pitch the tent, but the tide forecasts were for 7.5 feet, or something akin to “unremarkably average.”

This is where I have to stress that tide tables are forecasts, and tides in general are estimations. Just because the morning estimates are correct doesn’t mean they will be right tonight. I have passed several USCG mate’s and master’s tests where I had to calculate velocities and tides; it’s tedious and involved, and all of it is based on predictions.

Using the tide tables is fixed math, but the underlying estimates are part science and part alchemy and can vary greatly from reality.

Tide tables reference predictions at specific points. To get the tide prediction for a location NOT at those points, you have to average the nearest prediction points; or, you do what one does and you let a computer do that for you… in the end, though, whether you do it long-hand or let a computer do it for you, it is still a prediction and nothing more.

I jokingly called this new location “Camp Rebound” and it was the most sand-free I’d been in days. It had a lot going for it; mainly, it wasn’t Camp Windburn.

I was exhausted and once camp was set - the required windbreak constructed first - all I wanted to do was sleep. But the current was still running and the tide wouldn't be high again until 2305 (11pm).

Manu’iki’iki was tied alongside the steep, sandy western shore. The bow line was anchored in the dunes, and the stern line ran aft to a locally found shovel head that I drove into the sand.

However, the shovel head kept failing to hold under the strain of the wind, so I tied the bow to a stunted and struggling juniper bush and swapped out the shovel head for the bow anchor. Because the previous configuration failed several times, I was exceptionally wary and distrustful of holding fast to an ever-changing landscape and I wasn’t going to rest until he sat high and dry.

I set an alarm on my phone and tried to sleep, but my nagging mind forced me out to keep checking on the ever-changing state of things.

When 2300 finally rolled along I manhandled the canoe up on top of the dune and felt satisfied I wouldn't have to deal with that again for the next 12 hours - not until the full cycle of the ebb and flow of the current brought the next high tide.

The creek was a tempest of lapping wind waves, disconcertingly close - not more than twenty feet from where I pitched my tent.

On the marsh side of the dune, the water crept up through the evening as dark and silent as a nocturnal hunter.

I did my rounds, watching the time and waiting for the tide to visibly turn so I could finally sleep. I was mildly alarmed at how my dune had become a lone island - that tempest on one side, and the black, waveless sheet in the grass to the other… but the tide should turn any minute.

I could physically watch the water rise on the marsh side, a quarter inch at a time, slowly inward and upward, ever closer to my humble camp just a few feet away.

2305 came and went, but the saltwater kept inching upward. I felt a growing dread, and with each minute the unease grew.

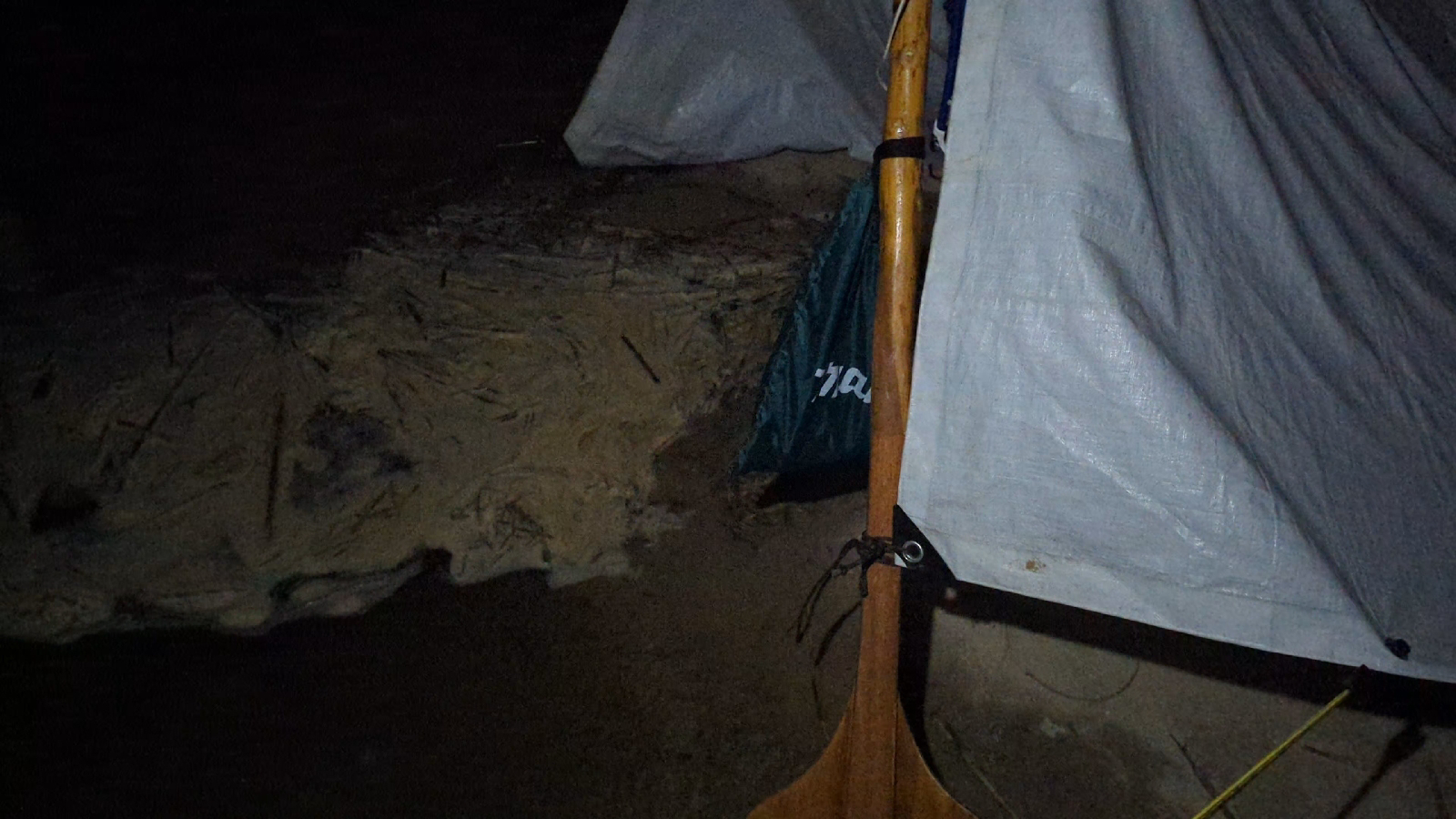

I had to act. Before the first of the waves breached the dune on the creek side, I moved the tent to the highest available spot, a sandspur-infested tangle crowned with dead marsh grass about the same size as the tent.

My biggest fear about moving the tent was that the 40-knot wind would take it, with the Thermarest and sleeping bag still inside, and hurl them one and all into the Atlantic.

At midnight the tide was still coming in. I again dragged Manu’iki’iki away from the eroding shore as the sand washed out from underneath him. Waves poured over the sands and rejoined the water in the marsh.

I made my last stand by the tent. I put the drysuit bag next to the fly opening, on top of my sandals, and watched as the last dry land around me disappeared under the rising water.

Waves washed the dune from under Manu’iki’iki’s bow and he rocked back and forth as the waves smacked his long, narrow hull. Only his stern remained on a dry lump of grass-covered dune, now a lonely little islet.

Around me, wind-ravaged white horses raged to the east, the 40-knot sustained blow howled out of the inundated marshes to the north, and the 200 yards of black, creeping water stood between me and the trees of the inhospitable tangles to my west. Isolated and beset dune peaks were caught between the hammer and anvil where the waters met and pulled them under, inch by inexorable inch, to my south.

And, the damnable din of the tent flogging!

My planned next and final step? Put the dry suit back on, climb in the drowned tent, and wait until dawn. But the tide finally stopped at 0020, almost an hour and a half after predicted.

I climbed into the tent at long last and discovered every single sandspur under the tent floor with my hands and knees as I worked my way into my sleeping bag. I fell asleep on a giant hump and a sideways incline, the sleeping bag slipping off the slick Thermarest pad like it was greased.

And I actually slept a little, until it started to rain (also not predicted).

The rain fly no longer worked; the wind had ripped out all the tent stakes and the entire rig was flogging around like a tube man at a used car lot. The rainwater soaked through the rain fly to the tent fabric with no resistance, and I woke up to the inside of the wet tent slapping my face over and over.

That was the moment I finally said “uncle.” I wasn't mad. I didn’t laugh. Nor did I react in any way… one moment I was still doggedly going to continue my trip no matter what and the next I was not.

Slap. Slap. Slap…

At dawn, I saw the extent of the changes to the landscape, wrought by the night’s king tide.

Four feet of the shore dunes along the creek disappeared. Dead marsh grass had moved.

In a landscape that never ceases to change, it was nothing. Just an unforecasted king tide. Move along, you tired and filthy little monkey, there’s nothing to see here. So what if a few thousand tons of sand moved around in the night?

Mother Nature on the Guale Coast is cold and merciless and takes care of her own affairs and my fate is all my own. I feed the crabs or the crabs feed me. The end.

Fleetwood showed up on the incoming tide in his aluminum-hulled powerboat to tow me back to Tybee through the cut that joins Little Tybee Creek to the Back River (Tybee Creek), a narrow little cut Laura and I hauled a jonboat through, pushing and pulling by hand one low tide in 2011, much as I had done my entire childhood.

A little bit of sun was up and the wind dropped to 20 knots, but it was still blowing and the margins for error were still fairly close to zero.

Manu’iki’iki wasn’t a fan of being towed, and although Fleetwood had just made a towbar for his boat (which he’d previously joked was for towing me back to his dock when I got my ass kicked), but it wasn’t installed, yet, so I had to tend the line the entire slow-go back.

If I paid out the right amount of line I could get Manu’iki’iki “in step” with the wake and he’d hold to the wave and behave; otherwise, he roamed side to side at will and had a mind of his own.

Back at the boat shed the sun was out and the wind was blocked by the entirety of the island canopy - it was a nice spring day, exactly the kind of day I envisioned when planning this adventure.

A lizard rode the entire ride from dock to Beach Hammock and back on the outboard’s steering cable. I scooped him up, gave him a short ride on my shoulder, and delivered him to a dry, bug-infested water oak. A kindred spirit.

My “trip down the Georgia coast” on Manu'iki'iki is, for the time, over.