With all due fanfare, the video of my canoe misadventure (a video version of the previous 3 blog posts) is finally done! If you're curious, it actually took me more time and energy to put the video together than it did to take the trip...

Way For A Sailor

A day in the life of a bluewater merchant sailor.

Monday, July 31, 2023

The Video Is Done!

With all due fanfare, the video of my canoe misadventure (a video version of the previous 3 blog posts) is finally done! If you're curious, it actually took me more time and energy to put the video together than it did to take the trip...

Wednesday, April 12, 2023

Tides Are Only Estimates

and, it continues... I had driven Manu’iki’iki up onto the raft of dead marsh grass to prevent being swept out into the Atlantic's chaotic breakers and breaking up on the sandbars at the mouth of Little Tybee Creek.

Standing there, the wind howling through the rigging and the spartina grass, it was time to put on the dry suit.

Eating slices from a salami, alternating bites with a hunk of gouda, I pondered the many different ways my next move could go wrong. Capsize, swept into the breakers and broken, swept into the breakers and broached, the wreckage piling up on Wassau Island’s southern shore…

I gave Fleetwood a status update and explained my current predicament. His recommendation was to wait for low tide, which jibed with what I thought best, so I got comfortable.

This wasn’t the first time I’d waited for water to come in or go out while in the marsh.

I sat on the rear deck of Manu’iki’iki, moving him out of the exposed mudbank as the water slowly dropped from the rapidly outgoing current.

At this point, I still generally trusted the tide predictions.

Gradually, a sizable sandbar at the mouth of the creek (noted only as a “changeable area” on my charts) was revealed by the dropping water level. I backed Manu’iki’iki out of the marsh where we’d waited and moved to the roomier real estate of the sandbar, scoping out Little Tybee Creek - or as much of it as I could see.

When I was convinced the current’s velocity had dropped and the ebb tide at last arrived, I braved the crossing with only the confoundingly relentless winds to contend.

It was an almost placid crossing, marred only by my lingering misgivings.

Beach Hammock is an elderly dune covered in palm trees, palmettos, live oaks, dune briars, cactus, yukka, and is surrounded by three distinct types of marsh habitat, all of which marked the land’s rising elevation where I landed.

Little Tybee Creek runs parallel to Beach Hammock and a line of dunes forms the south bank of the creek and bounds the marshes on that side of the hammock.

I opted to pitch camp on the dunes to avoid hauling gear through the marsh to the dense woods of the island proper; it also allowed me to tend to Manu’iki’iki as the tidewater began to flow.

I removed my bright orange PFD and drysuit and carefully put them away and thought confidently to myself, “I’m not getting wet today!”

I know that an exceptional spring tide could cover the area where I chose to pitch the tent, but the tide forecasts were for 7.5 feet, or something akin to “unremarkably average.”

This is where I have to stress that tide tables are forecasts, and tides in general are estimations. Just because the morning estimates are correct doesn’t mean they will be right tonight. I have passed several USCG mate’s and master’s tests where I had to calculate velocities and tides; it’s tedious and involved, and all of it is based on predictions.

Using the tide tables is fixed math, but the underlying estimates are part science and part alchemy and can vary greatly from reality.

Tide tables reference predictions at specific points. To get the tide prediction for a location NOT at those points, you have to average the nearest prediction points; or, you do what one does and you let a computer do that for you… in the end, though, whether you do it long-hand or let a computer do it for you, it is still a prediction and nothing more.

I jokingly called this new location “Camp Rebound” and it was the most sand-free I’d been in days. It had a lot going for it; mainly, it wasn’t Camp Windburn.

I was exhausted and once camp was set - the required windbreak constructed first - all I wanted to do was sleep. But the current was still running and the tide wouldn't be high again until 2305 (11pm).

Manu’iki’iki was tied alongside the steep, sandy western shore. The bow line was anchored in the dunes, and the stern line ran aft to a locally found shovel head that I drove into the sand.

However, the shovel head kept failing to hold under the strain of the wind, so I tied the bow to a stunted and struggling juniper bush and swapped out the shovel head for the bow anchor. Because the previous configuration failed several times, I was exceptionally wary and distrustful of holding fast to an ever-changing landscape and I wasn’t going to rest until he sat high and dry.

I set an alarm on my phone and tried to sleep, but my nagging mind forced me out to keep checking on the ever-changing state of things.

When 2300 finally rolled along I manhandled the canoe up on top of the dune and felt satisfied I wouldn't have to deal with that again for the next 12 hours - not until the full cycle of the ebb and flow of the current brought the next high tide.

The creek was a tempest of lapping wind waves, disconcertingly close - not more than twenty feet from where I pitched my tent.

On the marsh side of the dune, the water crept up through the evening as dark and silent as a nocturnal hunter.

I did my rounds, watching the time and waiting for the tide to visibly turn so I could finally sleep. I was mildly alarmed at how my dune had become a lone island - that tempest on one side, and the black, waveless sheet in the grass to the other… but the tide should turn any minute.

I could physically watch the water rise on the marsh side, a quarter inch at a time, slowly inward and upward, ever closer to my humble camp just a few feet away.

2305 came and went, but the saltwater kept inching upward. I felt a growing dread, and with each minute the unease grew.

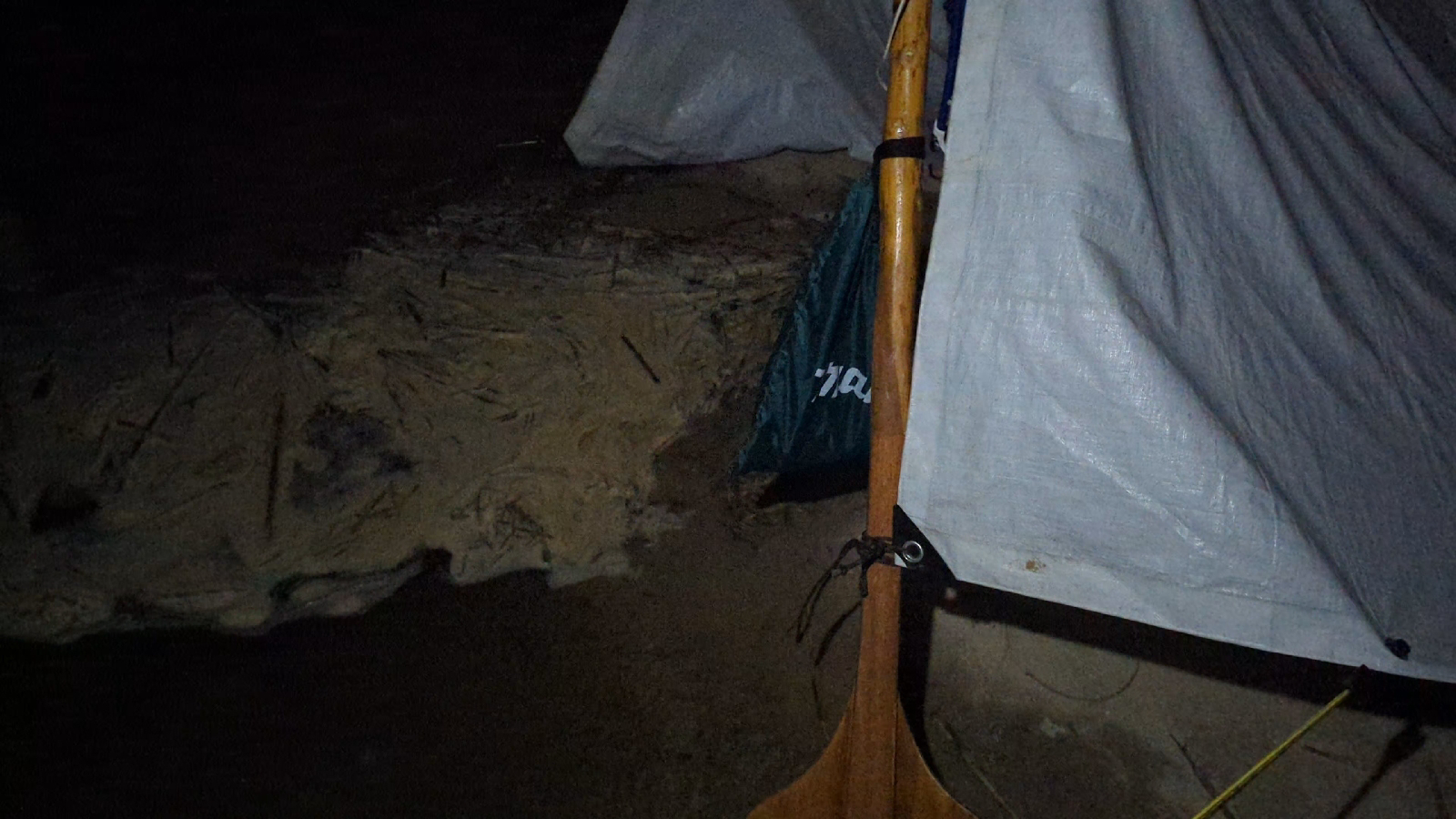

I had to act. Before the first of the waves breached the dune on the creek side, I moved the tent to the highest available spot, a sandspur-infested tangle crowned with dead marsh grass about the same size as the tent.

My biggest fear about moving the tent was that the 40-knot wind would take it, with the Thermarest and sleeping bag still inside, and hurl them one and all into the Atlantic.

At midnight the tide was still coming in. I again dragged Manu’iki’iki away from the eroding shore as the sand washed out from underneath him. Waves poured over the sands and rejoined the water in the marsh.

I made my last stand by the tent. I put the drysuit bag next to the fly opening, on top of my sandals, and watched as the last dry land around me disappeared under the rising water.

Waves washed the dune from under Manu’iki’iki’s bow and he rocked back and forth as the waves smacked his long, narrow hull. Only his stern remained on a dry lump of grass-covered dune, now a lonely little islet.

Around me, wind-ravaged white horses raged to the east, the 40-knot sustained blow howled out of the inundated marshes to the north, and the 200 yards of black, creeping water stood between me and the trees of the inhospitable tangles to my west. Isolated and beset dune peaks were caught between the hammer and anvil where the waters met and pulled them under, inch by inexorable inch, to my south.

And, the damnable din of the tent flogging!

My planned next and final step? Put the dry suit back on, climb in the drowned tent, and wait until dawn. But the tide finally stopped at 0020, almost an hour and a half after predicted.

I climbed into the tent at long last and discovered every single sandspur under the tent floor with my hands and knees as I worked my way into my sleeping bag. I fell asleep on a giant hump and a sideways incline, the sleeping bag slipping off the slick Thermarest pad like it was greased.

And I actually slept a little, until it started to rain (also not predicted).

The rain fly no longer worked; the wind had ripped out all the tent stakes and the entire rig was flogging around like a tube man at a used car lot. The rainwater soaked through the rain fly to the tent fabric with no resistance, and I woke up to the inside of the wet tent slapping my face over and over.

That was the moment I finally said “uncle.” I wasn't mad. I didn’t laugh. Nor did I react in any way… one moment I was still doggedly going to continue my trip no matter what and the next I was not.

Slap. Slap. Slap…

At dawn, I saw the extent of the changes to the landscape, wrought by the night’s king tide.

Four feet of the shore dunes along the creek disappeared. Dead marsh grass had moved.

In a landscape that never ceases to change, it was nothing. Just an unforecasted king tide. Move along, you tired and filthy little monkey, there’s nothing to see here. So what if a few thousand tons of sand moved around in the night?

Mother Nature on the Guale Coast is cold and merciless and takes care of her own affairs and my fate is all my own. I feed the crabs or the crabs feed me. The end.

Fleetwood showed up on the incoming tide in his aluminum-hulled powerboat to tow me back to Tybee through the cut that joins Little Tybee Creek to the Back River (Tybee Creek), a narrow little cut Laura and I hauled a jonboat through, pushing and pulling by hand one low tide in 2011, much as I had done my entire childhood.

A little bit of sun was up and the wind dropped to 20 knots, but it was still blowing and the margins for error were still fairly close to zero.

Manu’iki’iki wasn’t a fan of being towed, and although Fleetwood had just made a towbar for his boat (which he’d previously joked was for towing me back to his dock when I got my ass kicked), but it wasn’t installed, yet, so I had to tend the line the entire slow-go back.

If I paid out the right amount of line I could get Manu’iki’iki “in step” with the wake and he’d hold to the wave and behave; otherwise, he roamed side to side at will and had a mind of his own.

Back at the boat shed the sun was out and the wind was blocked by the entirety of the island canopy - it was a nice spring day, exactly the kind of day I envisioned when planning this adventure.

A lizard rode the entire ride from dock to Beach Hammock and back on the outboard’s steering cable. I scooped him up, gave him a short ride on my shoulder, and delivered him to a dry, bug-infested water oak. A kindred spirit.

My “trip down the Georgia coast” on Manu'iki'iki is, for the time, over.

Tuesday, April 11, 2023

Awash

My entire second day on the narrow spit of sand dangling south from Little Tybee was spent in a howling wind from the north. I scoured the beach and the dunes for heavy timbers to anchor the tarp I rigged as a windbreak for the tent.

The further I wandered, the better the timbers I found... the better the timbers, the heavier they happened to be. So trudging up and down the beach, alternating my loads from one shoulder to the other, I felt like a modern-day Sisyphus struggling against the wind and the sand.

The WX channel on my handheld radio declared measured wind speeds of 25-35 knots and gusts up to 45 - I’d argue it was slightly higher where I was but I didn’t have an anemometer to quantify my experience-fed suspicions.

To be fair, every wind is 35 knots when you’re rigging up a tarp.

Once I had a semblance of order, I cooked a hot meal, hot both with fire and habanero and jalapeno peppers. I packed wool base layers as part of my emergency kit and I didn't expect nor intend to wear them, but I had them on, plus almost every other item of clothing from my gear bag. The temperature fell from the mid-80s (F) when I set out to the mid-40s.

As long as I stayed dry I was safe from hypothermia.

I had it in mind that the fastest, most expeditious way out of the predicament I was in (stranded for the duration in a crappy location) was to portage Manu’iki’iki across the dunes to the marsh side of the spit and make my escape on the next high tide.

At dusk I undid the lashings holding the iokos to the wa’as and carried the amas and iokos across the dunes, stopping every so often to give my sore back and chaffed skin a break - I was beginning to suffer from all the timbers I’d scavenged that day.

I then dragged the canoe across the dunes using crab trap floats I found in the tide line as rollers. When the rollers became untenable, I just dragged the canoe through the sand.

I left Manu’iki’iki next to a marsh mudhole in pieces mostly confident he’d be there in the morning.

That night was slightly better than the night before in terms of thunderstorms and precipitation, but the wind picked up a couple handfuls of additional knots and buffeted the windbreak and tent mercilessly.

With the wind came the familiar swirling cloud of sand in the tent - less of it than the night before, but in terms of losing battles, my great efforts to outsmart the sand was a brave and valiant but utterly failed effort.

Growing up, we called this super-fine sand “sugar-sand,” as it has a grain and texture much like confectioner’s sugar. This small size allows it into every single imaginable opening (USB ports, stove burners, ears, etc.) but contrary to expectations, is exactly like a large grain of sand when it’s in your food and crunching between your teeth.

At one point during the night, my imagination led me to believe the sapling trunk I propped up with bamboo to form the frame of the windbreak might conceivably slide across the sand and drop that sapling pole on my head.

I was relying on the sheer weight of the sapling to hold the windbreak in place against the wind (it was about 100 lbs) but wind has a funny effect on sand: It scoops it out on the windward side, and deposits it on the leeward side (in this case, into my tent). It will undermine any stationary item, weight be damned.

I also had 120 square feet of sail in the form of a tarp lashed to the sapling. As badly as I wanted to stay in the sleeping bag carefully balanced on top of the slick and narrow Thermarest, the calculus just didn’t work in my favor.

So at about 0200, I was out in the dark fighting the goblins in my head by running lines to help anchor the sapling so that when erosion finally won its relentless war against me, it didn’t drop said sapling on my head and destroy both the tent and my sleep.

At 0700 Fleetwood called. He was monitoring the weather situation and he and Bill, both having spent years picking the bones off dead boat carcasses as marine salvors, were of a mind to come and snatch me off the island.

The problems with this were 1) the only way to reach me was from the ocean side of the island, and that ocean was pounding surf; and 2) I was fine, if not comfortable, and I didn’t actually need rescue. I would wait it out and then continue on with the trip I intended.

Unbeknownst to me, the storm front had stalled, but the forecasts still confidently declared the winds would die down to something reasonable by the end of the day.

I was convinced I needed a drill to fix my broken wa’a so I could escape that damnable spot - what I first named “Camp Storm Dune” and now called “Camp Windburn” - but I left my drill behind. I did, however, have several knives.

After a brief discussion with Fleetwood, I went out with a knife and dug a hole through the 1-½” wa’a by spinning the knife and gnashing my teeth.

I dug from both sides and met in the middle, then lashed it with a piece of Dyneema and tensioned it to excess with a Spanish windlass.

Fixed!

Back at the tent making coffee, I noticed the area one dune south of me and the area one dune south of Manu'iki'iki had both been overrun by breakers while I'd slept.

By taking refuge against the wind I chose the lowest spot behind the biggest dune. That low spot was actually lower than the areas that were swept over by breakers.

Down on my hands and knees and sighting from the tent, I saw there was only an inch or two of rise in the beach that prevented me from waking up the previous night in a foot of water had that meager rise been breached.

The washout to my south now connected the mudhole to the Atlantic only a few feet from the high spot where I'd unceremoniously piled Manu’iki’iki’s parts.

This changed everything. I had to relocate.

Should I make a lateral move and carry all my gear up the beach? A quarter mile up, the tallest dune sported a lone palm tree and a tangle of beach briar.

Or should I load up the boat and escape across the marsh as I’d planned the night before, taking my chances that I'd find a better place altogether?

I went with “escape across the marsh” which meant I had to get it in gear, pronto!

I had no time to spare - the tide was three-quarters in. I did the fastest camp breakdown, gear pack up, and cargo loading imaginable and without a single look back, shoved off.

A nearby hammock to windward looked inviting. As I kicked off, I pointed my bow windward and paddled like mad and was immediately blown south by the 35-knot north wind and into the thickest tangles of marsh grass I was trying to avoid.

What followed was a half-hour of curses, frustrations, and loudly-expressed and inconsolable angst; it was a mercilessly unfavorable situation, and my invective continued without interruption until I broke out onto a small creek with a false sense of relief.

I was out of the frying pan, at last!

Under the bare mast I discovered an interesting thing about Manu'iki'iki - he will simply lay ahull with the ama downwind. This is both useful to know and handy in a pinch in the right situation.

For those who do not know, you're laying ahull if your boat is broadside to the wind and moving sideways.This was not the right situation to be laying ahull.

I paddled like hell on the starboard side, and alternatingly back-paddled on the port side, getting his bow downwind. We flew along, his narrow canoe shape like a water dart, hitting about 7 knots until it all went sideways on me, literally, and Manu’iki’iki would lay ahull again.

After a few minutes, however, I got us making way using the steering oar. I hadn’t rigged up the giant rudder for this jaunt as it is massive and unwieldy and I didn’t trust myself to keep it from fouling me up again as it did before, during the ill-fated knockback in the surf. And the thought of dragging it through the mud and marshgrass wasn't pleasant, either.

Seven knots brought me to the mouth of the creek where it dumped me into Little Tybee Creek in just a few short minutes.

Little Tybee Creek is usually a wide, gentle-moving body of water between tides. At high tide, it's a wide body of often still waters, darkened in places by zephyrs moving across its surface but overall a respite from the ocean swells that break on the beaches and bars nearby. At low tide, it's a network of small creeks wandering around sandpiper-covered sandbars and mudflats bejeweled with periwinkles.

This day it appeared deceptively flat and dangerous as the current and wind conspired to take anything and everything along at the greatest speed in one direction; the storm-wracked Atlantic was another mile down and visible as a dancing white froth. If I went into that swift running current I would be in the washing machine in very few moments, and if that happened I wasn’t getting out of it in one piece.

On impulse and with an adrenaline-fueled sense of self-preservation I drove Manu’iki’iki up onto a raft of dead marsh grass at over five knots just before being swept out into the Atlantic.

I had no idea how in the hell I was getting out of this.

I'm going to leave it here for the moment so I can get this posted and I'll continue to write about what happens next for tomorrow, but if you think it couldn't get worse you'd be laughably and sorely mistaken.

So until tomorrow...

Sunday, April 9, 2023

Shipwrecked!

Saturday, April 8, 2023

Manu'iki'iki's Story

The Back Story

While on the M/V Matson Manukai in 2015, I had the idea that designing and building a boat and heading down the coast of Georgia was something I wanted to do. I used to daydream about taking off down the coast while wandering the beaches on the south end of Tybee when I was a feral beach rat, and I’ve never really outgrown that daydream.

I designed three boats for those shallow, coastal waters in my head while standing watch: an expedition stand-up paddle board, a deep-vee wooden powerboat, and a barge with a commercial-like front house.

So of course I didn’t build any of those; not exactly. Instead I built an outrigger sailing canoe.

In all fairness, I chopped the freeboard off and put a stand-up paddleboard deck on it, but it’s still a sailing canoe… a super shallow draft canoe with a kickup rudder and leeboard.

To power it, I built a solar outboard motor and 36v battery (yes, a home-made battery), made or altered three paddles (a backup for the backup!), and refabricated a head sail and a mainsail. Then I threw it in the water at Shilshole Bay and gave it a cursory test.

Aaaaaand… then I started two large projects.

So I put Manu’iki’iki into my storage unit and within minutes he was buried in - quite literally - 72 cubic yards of rockwool insulation.

That was two years ago.

For those who think I typoed: I grew up with boats being “she” and did not know there were “he” boats. As it turns out, Micronesian sailing canoes are male.

Here are some interesting things about this project:

Manu’iki’iki is built with 100% reused and reclaimed lumber.

The hull and iokos (the curved “sticks” that attach the outrigger to the canoe) are from a cedar deck I replaced with composite decking years ago;

The two bulkheads are plywood from the deck of a long-since departed inflatable dinghy Tim gave me after the dinghy gave out;

The Wa’a (the athwartships members the iokos lash to) are from a piece of dunnage saved from a project I did for a Hawaiian architect - which turned out to be Sitka spruce;

The rudder is from a shelf board of an unknown type of cedar ripped out of the root cellar in our house, put in by either Laura’s grandfather or great-grandfather;

The mast step and ama uprights are from a piece of handrail off the house I further turned with a lathe I made from a drill motor and skateboard bearings and is clear fir;

Assundry “sticks” used to tighten lashings are from a madrona tree Laura and I planted in the yard;

The deck is a combination of the red and Port Orford cedars I used to make the hull and three pieces of cut-off and saved Sitka spruce from a boom I made for Stu’s sailboat Ishka;

The bamboo all comes from a harvest undertaken by Andy from a neighborhood patch - he brought the 30’ sticks over to my house (leaves and all) on an electric “one-wheel” through the streets of Seattle in one of the more awesome bits of randomness associated with this boat;

The boat is named Manu’iki’iki (“really little bird”) in part because one of “my” Steller’s Jays hung out with me the entire time I was building the hull, hopping along the ground or in the trees and bushes surrounding the boat shed, snacking on whatever birds snack on, unannoyed in the least by the noise and the dust;

The sails are from a marine garage sale Laura and I went to in 2010 which began their lives as larger sailboat cruising sails. I have used the fabric for many projects over the years and saved remnants of fabric for “just in case” purposes; these were highly modified sail “corners” re-imagined with Ivy’s hand stitching to make up the main and a small jib;

There is not one piece of metal used in the construction of this boat - no screws, nails, or rigging pieces.

I’m sure to be missing some random bit of information here, but I’ll update as I think of it.

Currently, I am on Tybee Island and Manu’iki’iki is at the WBG Marine shop where he’ll undergo a few small modifications and reassembly, beginning in the morning. If I don’t go out paddling on a board with Fleetwood, that is… he offered and I might just take him up on that… I do have a full and a partial wetsuit with me and it would be a crying shame to haul them all this way and then not use at least one of them.

The morning will tell.

Thursday, March 30, 2023

Once More Into The Breach

We steamed northeast from Darwin, Australia, crossing the point where the equator meets the international date line, a transit so dull I no longer remember anything but the rage I felt toward management; a rage that still burns hotly deep in the ashes of my psyche, but out of sight and out of mind these last few years.

In May, 2020, I went down the gangway in Oakland, California at last, and the entire world was shut down from the Covid-19 pandemic. The company gave me a cloth mask and an "Essential Worker" letter as I signed off Articles and sent me on my way, no love lost between us.

My reintegration process felt like I’d landed in a different timeline. I rented a car and listened to audiobooks as I drove the Pacific Coast Highway north to Seattle on utterly deserted highways.

Gas stations were empty. Lights were off in all the stores. There were no pedestrians on the sidewalks; when I did see lone solitary figures walking their dogs or hurrying along with shopping bags swinging in time to their strides, their faces were bizarrely obscured by masks.

I have said it a dozen times here on this blog or to any random person on the streets with ears pointed in my general direction – to be on a ship for seven months is to be in a coma dream that never ends, each day a slightly varied repeat of the one before, and when you finally wake, you find the world moved on without you; the displacement is jarring, the feeling of isolation is absolute, and for weeks you're a fish who finds himself outside the aquarium, looking in.

With the fog of that timeless sleep still thick in my head I transited the coast northward. While crossing the Pacific on its longest axis, I had crossed into a different, stranger, and shittier timeline – I had wandered onto the set of a post-apocalyptic zombie movie that made waking from the coma more visceral and surreal.

I went through the motions of renewing my sea papers and taking a basic safety refresher course, but my disillusions with my maritime career had grown so pronounced that it was with relief that I got my general contractor's license again. I began working on a major new house project and doing projects for a series of clients, ranging from the not-so-satisfactory to the best of the best. Seems I was too busy to go back to sea anytime soon.

And into this years-overdue update comes a project that has me firing up the Way For A Sailor blog again… a combination of a lifelong dream and a plan hatched in 2015 while staring at the Pacific Ocean on the 12x4 watch: building an outrigger sailing canoe and taking it down the coast of Georgia.

Stay tuned; details to come.

Saturday, April 25, 2020

Down, Down, Down Under

Thursday, April 2, 2020

At Long Last - The Oz

Saturday, February 29, 2020

That's How We Rogue

The trip from Kwajalein to Guam was notable for the amount of alcohol and mayhem taking place as our ship full of empty containers rolled uncomfortably in low seas and moderate swells, her righting moment so high that we snapped from side to side without a tender moment. The amount of work that got done coincided with the sobriety of the mate and bosun, so for every busy day there was a slow day.

The two Hawaiian sport fishermen - the bosun and the oiler - pulled up Mahi Mahi (dorado) from the stern on hand lines and make-shift out-riggers as we slow-belled between islands; they BBQ'd the catch (that, or meat raided from the freezer) daily. The picnic table on the poop deck became the official scuttlebutt where everyone came to find out or share the latest info on what our possible schedule would be, like we’re a tramp.

|

| The jury-rigged out-rigger for a fishing line |

|

| Mahi Mahi, aka dorado |

I got one grocery run done and a quick swim in my snorkel spot before departing. No one was happy about the short stay. It was enough to dampen the mood a little, but the weather was nice and the chief mate restocked the dwindled grog supplies, so the dampened mood dried out quickly and soon the BBQ’s were fully manned while I was on my 4x8 watch. I would yell down to them from the bridge wing, and one night the mate broke out a hose and gave them some rain.

And then the flat seas decided to do what flat seas do: unflatten.

I went to bed one night after a watch spent on an ocean made of glass. I woke a little after 0100 when the bow was slapped by a sizable swell, causing the ship to pitch and roll noticeably. We didn’t stop rolling after that hit, and by morning everyone had lost any sleep gains they might have enjoyed from the previous nights’ smooth sailing.

After a morning watch spent rolling 25 degrees, I went below to secure my quarters and my work assignment. The tile for my head repair job was out on an upper deck in a bucket (the main deck and poop deck were secured for weather), and as I poured off the soapy water the flooring had been soaking in, the ship rolled so severely I began sliding across the deck. The 30 or so cases of bottled water stored on that deck soon followed.

|

| Snap-rolling along. This is approx. 12-15 degrees of roll. |

The bottles broke apart on the rail and many of them went immediately overboard.

The fridge in my secured quarters spilled it’s fresh stocks of yogurt and milk onto the deck and an avocado burst. The Bosun met me in the passageway with a pile of trash bags and while he went down to the mess hall, I went to the bridge - both places looked destroyed.

We lost all our plates down below, of course (I only saw paper plates and bowls after that). All the condiments hit the deck and went everywhere. Chairs and microwaves flew; one microwave didn’t survive.

Up on the bridge where I helped clean up, our bucket of used coffee grounds mixed with broken mugs, manuals, charts, pens, a blender, and more- all of which hit the deck on the first roll and then slid, mixed, and piled up against the bulkhead on the second.

Oddly, all the mess on the bridge seemed to pile up on the port side bridge wing door while I’d almost gone over on the starboard side.

One sailor face-planted into a bulkhead and complained for a week about pain. The store room was knee deep in fire extinguishers, mattresses, line, valves, safety gear, and fasteners. The dry stores was a pile of cans, bags, and bottles.

The deck gang responded en masse and within a couple hours it was impossible to tell anything untoward had happened… but it was my second encounter with a rogue wave and I will not forget it anytime soon. A 30 degree roll is what it takes to throw me out of bed; a 40 is enough to remember.

We arrived at the anchorage in LaBuan, Malaysia, without any further incident.

The last week was spent securing the ship for layup. We made canvas covers for vents; disposed of expiring food, stores, and medicine; cleaned and waxed decks; crane lifted generators and fuel aboard; and we accommodated the Malaysian crew now living aboard the ship in a house they constructed of mahogany studs and luan marine ply on the deck where our scuttlebutt BBQ had been.

|

| Boats of LaBuan harbor |

|

| M/V Kamokuiki at anchor, as seen from the launch |

|

| What a sailor does with spare airplane parts, LaBuan harbor |

|

| Lamp post in an estuary of Malaysia |

|

| I'm pretty sure this boat is from Sumatera - Boats of LaBuan Harbor |

|

| Boats of Labuan Harbor |

|

| Supply vessels at anchor in the petroleum services harbor, LaBuan |

The flight back to Seattle involved a prop plane, three jets, 40 hours of airport travel, and having my papers inspected two dozen times by the immigration officials of every country I skipped and hopped through to get back to the USA.

I arrived home yesterday morning, but now trying to recount it all, it seems like a dream… a coma dream… something that all happened to someone else or not at all. It’s as if I went to sleep last night and had a vivid dream, then woke up this morning tired, sore, and distracted.

With a foul mouth.